$745.00 Original price was: $745.00.$447.00Current price is: $447.00.

1 in stock

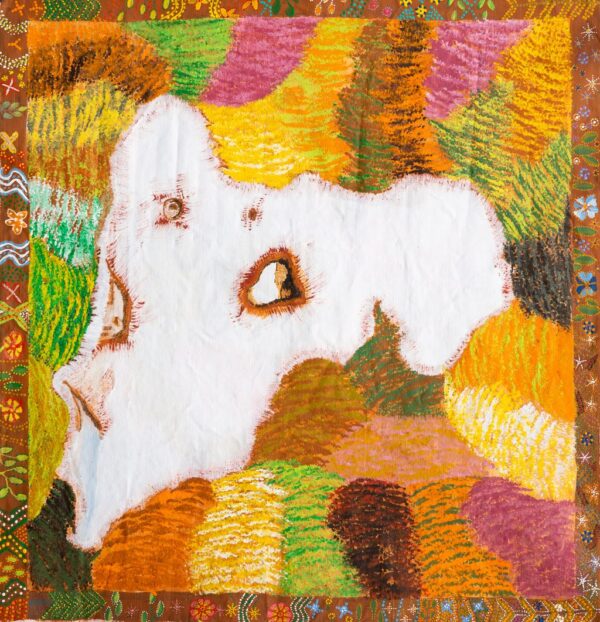

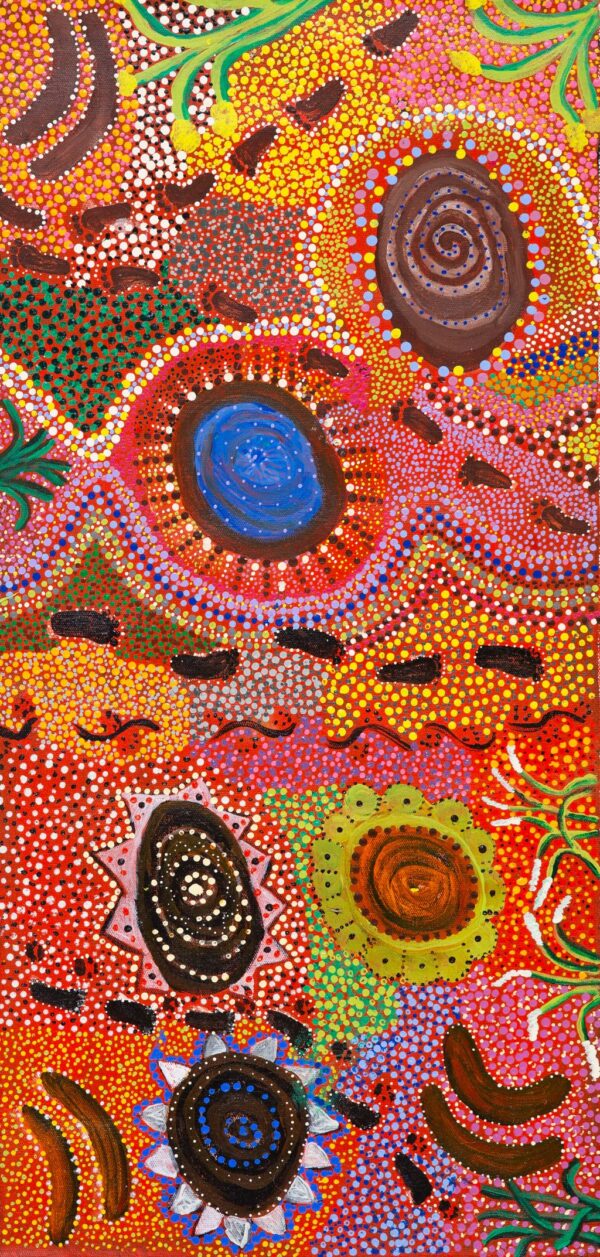

Noreena Kadibil

Acrylic on Canvas

61 x 61 cm

Year: 2024

24-1081

Karlaya (Emu) and Kipara (Bush turkey) Jukurrpa (Dreaming)

“This is the story of the Karlaya (Emu) and Gibbra (bush turkey). They could both fly until the gibbra tucked its wings telling the emu it couldnt fly and that they should cut their wings too, the emu was tricked by the gibbra and cut its wings. The emu felt very sorry for itself. The emu then hid all but two of its chicks telling the gibbra its hard to feed any more, the gibbra was tricked and killed all but two of its chicks, the emu then called back the rest of their chicks. That was the pay back.” -Noreena Kadibil The term Jukurrpa is often translated in English as the ‘dreaming’, or ‘dreamtime’. It refers generally to the period in which the world was created by ancestral beings, who assumed both human and nonhuman forms. These beings shaped what had been a formless landscape; creating waters, plants, animals, and people. At the same time they provided cultural protocols for the people they created, as well as rules for interacting with the natural environment. At their journey’s end, the ancestral beings transformed themselves into important waters, hills, rocks, and even constellations. Kipara (Australian Bustard, bush turkey) are ground-dwelling, large, speckled grey-brown birds found in the plains of the Western Desert and across northern Australia. Kipara fly long distances in the search of food, and were once widespread among the plains of Australia. However, following colonisation they have become increasingly rare. Kipara often travel in groups, and walk slowly, picking at food such as jinyjiwirrily (wild gooseberry, desert raisin), and are usually found at twilight and after dark. Kipara are known by Martu to be attracted to burn areas in the nyurnma (freshly burnt) and waru-waru (green shoots and young plants are sprouting from burnt areas) stages. Traditionally, kipara were stalked and then wounded whilst taking off using a karli (boomerang). Today, kipara are generally hunted with rifles from vehicles, enabling a close range approach. Also depicted in this work are karlaya (emus); large, flightless birds endemic to Australia, and found across the whole country. Emus have been hunted by Martu people as a source of bush tucker from the pujiman (traditional, desert dwelling) era through to today. Typically, emus were tracked using their distinctive jina (tracks, footprints). Acute skill in track observation and identification traditionally possessed by Aboriginal people developed directly in relation to their past hunter-gatherer existence, when survival depended in large part on the successful tracking of hunted animals. In the absence of an actual animal sighting, tracks act as an identifier that an animal was present, which were then followed to the animal’s location. Once caught, the emu and its eggs were consumed, fat was harvested for several medicinal applications, bones were shaped into tools, feathers were used for adornment, and tendons substituted for string. During the pujiman period, Martu would traverse very large distances annually in small family groups, moving seasonally from water source to water source, and hunting and gathering bush tucker as they went. Whilst desert life has moved away from mobile hunter-gatherer subsistence throughout the course of the twentieth century, bush tucker continues to be a significant component of the modern Martu diet. Hunting and gathering bush tucker remains equally valuable as an important cultural practice that is passed on intergenerationally. Though hunting and gathering implements have been modernised, methods of harvesting, tracking and the use of fire burning to drive animals from their retreats are still commonly practiced today.

Sign up to Martumili Artists’ mailing list to receive artist news, special offers, and shop updates.

Martumili Artists warns visitors that our website includes images and artworks of Artists who have passed away which may cause distress to some Indigenous people.

Martumili Artists acknowledges the Nyiyaparli and Martu people as the Traditional Owners of the land we live and work on. We also acknowledge the Traditional Owners throughout our country and our Elders; past, present and emerging.